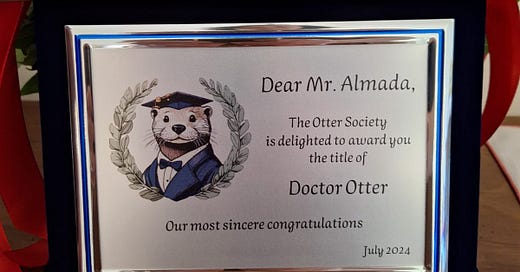

Hello, dear reader, and welcome to another issue of AI, Law, and Otter Things! Last Friday, I finally defended my PhD dissertation, titled “Delegating the Law of Artificial Intelligence. A Procedural Account of Technology-Neutral Regulation”. It was a lovely experience, being able to present my work to a surprisingly large number of friends and strangers, and discuss it with a panel of scholars I deeply admire. And, thanks to one of these coincidences of life, that was also the day in which the AI Act was officially published as Regulation (EU) 2024/1689. All in all, a pretty big day.

Today’s issue is not about my ongoing research. Instead, I want to talk a bit about my approach to research. After this meta rant, I will share some readings that I see as a good introduction to questions of law and technology. Finally, I share a few links to open calls and events.

Research as bricolage

One of my favourite things about academia is that I have the opportunity to contribute to debates I find interesting (such as, e.g., the one surrounding technology-neutral regulation). To do so, I (or anyone else), must balance two aspects that are not conceptually incompatible but can be tough to reconcile given that we have limited time in the real world. On the one hand, a contribution to any debate must engage with what has already been said on the topic. On the other hand, a contribution must bring something new to the table, so that we are not simply restating previous utterances. In the following paragraphs, I want to focus on the latter requirement.

In my view, the secret to being an interesting scholar was spelled out by Terry Pratchett: “Ninety percent of most magic merely consists of knowing one extra fact.” The most thought-provoking scholarship I read comes from a variety of backgrounds, methodologies, ideological standpoints, and other variables. But what makes them so powerful is that they make us think that something we previously saw as irrelevant, or at most a minor factor, is central to what we are talking about. For example, David Lehr and Paul Ohm’s Playing with the Data (2017) marshals knowledge about software development processes to explain why lawyers should look more closely at various technical decisions. In doing so, they not only address specific legal issues, but show how other people might do the same in their own problems of interest.

There are many ways one can add something new to ongoing conversations. A scholar might draw from their lived experience to raise questions and supply new perspectives, for example by bringing to the fold practices that are not well captured by existing models of a process or perspectives that have been traditionally excluded from discussions. Or they might bring insights from established academic literatures that are not usually seen as part of that conversation. These and other entry points might allow you, the scholar, to find something that goes beyond what other people have already said. And so, bit by bit, scholarly debate becomes richer once the “irritants” brought by those sources are properly situated within the debates of a scholarly community.

To the extent I say something interesting, it is in a large extent due to the second approach introduced above. I read broadly, often about things that are not usually of interest to legal scholars, and as a result I occasionally stumble into things that seem to be relevant to discussions that we are having within legal scholarship. This bricolage resonates with my lack of inclination towards a hedgehog-like focus on a single topic, and it helps me make the best of what I learned across the various false starts and dilettante passions I cultivated over the years. And it also helps me find a unique voice, as other people can enrich the conversation by bringing other points of view and knowledges to the mix.

Because of the way I think about academic knowledge production, I don’t think there is a single path towards becoming a researcher, not even within a narrow specialism. There is a need to have some shared background—otherwise there is no dialogue, just people speaking at cross-purposes—but too much emphasis on creating a shared “field” or “discipline” is a sure-fire way to create an intellectual monoculture. Still, in the sections below I will suggest a few readings that helped me set off on my path. Hopefully, that can work as a tasting menu for you, the reader: if you find something that clicks with you, then by all means try and bring it into your own perspective. Otherwise, just keep exploring other sources. And we will all be better off for it.

The hitchhiker’s guide to law and tech

When I started law school, I wasn’t planning to study technology law, for a few reasons. In part this was because I was just leaving a budding career as a data scientist, partly because I wanted to do something else of my life. But another factor that influenced my initial impression was a fear of being stuck into a box. Most of the works on law and technology that I was familiar with were carried out by intellectual property lawyers, a field that I’m not particularly fond of even today. It was only at the late stages of the legislative debate surrounding Brazil’s data protection law that I was finally persuaded that I could put my technical background to use and still do something that interested me from a legal point of view.

Almost ten years later, technology is anything but a niche interest in the law. Quite the contrary: it seems to have creeped everywhere, not just out of hype but also because digital technologies are embedded in the most diverse aspects of our social lives. So, I find myself hearing quite often the question How can I get started with the technological side of things? Often, it is accompanied by follow-up questions, ranging from the dismissive Does technology really matter for understanding the law of [X] these days?1 to the scared Will I need to learn programming or advanced math?2 There is no universal answer to these questions, I think.

Still, I would like to suggest a few resources that can help people with legal training in their engagement with new technologies (especially digital ones). It is necessarily an incomplete list, but it should give you a feel for methods that can be useful in finding out exactly why (or whether) technology matters to your questions of interest and understanding how that matters (or should matter) in legal terms.

Lee Vinsel, ‘Start Where the Pain Is: Notes on Topic-Selection in Technology Studies’ (Peoples & Things, 4 May 2024).

How should we decide what to study? A standard formula in technology law goes like this:

Find an “emerging technology”

Do a review (or speculate) about its societal implications

Examine whether existing legal frameworks can cope with the perceive risks (or opportunities of those implications)

Offer policy recommendations to address perceived gaps

Lee Vinsel is not a lawyer, but an STS scholar. Still, his short blogpost provides an alternative vision that technology law researchers should not ignore: focus on issues and then go to the technologies, not the other way around.

Przemysław Pałka and Bartosz Brozek, ‘How Not to Get Bored, or Some Thoughts on the Methodology of Law & Technology’ in B. Brożek, O. Kanevskaia & P. Pałka (eds.) Research Handbook on Law and Technology (Edward Elgar 2023).

A more legally-oriented paper on how to find an interesting research question in law and tech (and remember to probe your assumptions!) and how to search answers for it. I particularly appreciate its treatment of “variation” as both a method and an answer to technology law questions.

Lyria Bennett Moses and Monika Zalnieriute, ‘Law and Technology in the Dimension of Time’ in Sofia Ranchordás and Yaniv Roznai (eds), Time, Law, and Change: An Interdisciplinary Study (Hart Publishing 2020).

My favourite treatment of an ages-old question: is the law doomed to always play catch-up to technological change? (Spoiler alert: nope.)

Margot E Kaminski and Meg Leta Jones, ‘Constructing AI Speech’ (2024) 133 Yale L J 1212.

From within legal scholarship, Kaminski and Jones propose an alternative to the standard formula: looking at the “legal construction of technology”, that is, to how legal values, institutions, and objects contribute to how we make sense of technological possibilities. This framing allow us to avoid a reductionist view, in which the evolution of legal systems is somehow determined by technological developments.

Rebecca Crootof and BJ Ard, ‘Structuring Techlaw’ (2021) 34 Harv J L & Tech 347.

Another work that focuses on the methodology of law and technology. In contrast with the previous article, Crootof and Ard offer a three-stage framework that distinguishes between varieties of legal uncertainty related to technology, discussing the potential legal responses to those uncertainties.

David Edgerton, The Shock of the Old: Technology and Global History since 1900 (Profile Books 2019).

Another writing by a non-lawyer (this time, a historian), who shows us how the technologies that often matter the most for our lives are not always the fancy ones that capture our attention. Looking at older technologies is essential if we are to understand how society works and how societal dynamics can change.

Events and job openings

The universities of Padova, Tübingen, and Maastricht are hosting a workshop on harmonized standards in EU digital regulation. The workshop will take place in Padova (Italy) on 14-15 November 2024. Abstracts should be sent to Professor Annalisa Volpato by 15 August 2024.

The AlgoSoc project invites abstracts for their 2025 conference The Future of Public Values in the Algorithmic Society. Abstracts are due by 30 September 2024, and the event will take place on 10–11 April 2025.

Katharina Isabel Schmidt at the Max Planck Institute for Comparative and International Private Law in Hamburg is hiring a post-doc for the research group “Artificial Justice”. Applications for this 3-year position are due by 31 July 2024, and the selected candidate will start on 1 September 2024 or after.

Eduard Fosch-Villaronga at the Leiden University is hiring a Postdoc on Law, Robots & Society. Applications are due by 23 August 2024, for a period of 3 years starting on 1 October 2024 or thereabouts.

The University of Toronto is hiring an Assistant Professor in Law, AI and Technology. Applications are open until 16 September 2024, with an envisaged starting date of 1 July 2025.

Thank you very much for reading this newsletter! If you enjoyed it, please consider subscribing (for free) in order to receive future issues:

Please don’t hesitate to hit the “Reply” button or contact over social media to keep the conversation going. See you next time!

The response is usually “yes”, but more often it matters in the details of how law works rather than by radically configuring the underlying normative debates.

It depends on what, specifically, you want to do. Programming can be a stimulating intellectual activity, especially if you like puzzles (I don’t). But for the purposes of legal analysis, I would say that “learning to program” is a misguided goal. It does not yield as many insights as one might hope (just like a programmer learning “a little about law” hopefully teaches them enough to know when to contact the legal team rather than trying to do their work), has considerable opportunity costs, and often leads us to think about technology in terms of “making things work” rather than more critically. So, by all means, take the time to learn how to program. But that is neither necessary nor sufficient to think about technology from a legal perspective.

Congratulations!! I’m pretty sure that the was an amazing teaching journey (as difficult as well)! 👏🏼🥂